“Let me stand aside, to see the phantoms of those days go by me, accompanying the shadow of myself, in dim procession. Weeks, months, seasons, pass along.” – Charles Dickens

Alfred Standard, Yarmouth Beach, Norfolk, 1847; Great Yarmouth Museums; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/yarmouth-beach-norfolk-1980

Embarrasingly late to the party I finally picked up my first Dickens novel. Given that Dickens himself said ‘Of my books, I like this the best’ I felt David Copperfield was a perfect place to start. I was right. The span of this story is remarkable, beginning with Copperfields fraught childhood through times of poverty, despair and betrayal to prosperity, love and resolution. Through many twists and turns we are taken on a journey encountering characters’ hilarious, grotesque and inspiring. Throughout David Copperfield the complexities of the mid-Victorian world are revealed and the essence of life in this world so different to ours today is made real.

I could spend pages picking apart Copperfield’s childhood suffering under the Murdstones, Mr Pegotty’s search for Emily or the battle against Uriah Heep, but rather than summarise these plot points I’m going to take a look at the themes and curiosities that impacted me most when reading Dickens’ David Copperfield, so without further ado…

Language

It’s English dumbo. Well, yes and while we don’t encounter as many head scratchers as we would in a shakespearean scene, there are many subtle (and often not so subtle) differences in the use and meaning of words that we need to pay attention to. Most people won’t admit it but there’s no shame in grabbing your phone to look up a ‘wtf’ word every few pages. I won’t lie I had to google ‘amanuensis’, ‘supernumerary’ and ‘rhapsodical’ to name a few.

However, difficulties in understanding also pertain to the words we already know and share with Dickens’ victorian contemporaries. The words ‘wonderful’ and ‘awesome’ for instance, often mean something closer to ‘horrifying’ when said event inspires wonder or awe at the horror of what has taken place. Or take a passage where Miss Mowcher repeatedly says of herself in a conversation with Copperfield “Ain’t I volatile?” which in this context translates more as ‘Ain’t I cheeky?’ If we took the word volatility to mean what it does today we’d assume she had a violent disposition or some kind of borderline personality disorder. Oh, and I may be wrong, but I assume the ‘Ketchup’ Mrs Micawber refers to is something a tad different to Heinz.

History and context are incredibly important in understanding these characters and elucidate how people were actually speaking, writing and indeed thinking in mid-victorian times.

Race, Class and Empire

Reading Copperfield with a historians eye I couldn’t help but be aware of the context of the British Empire and Victorian attitudes concerning race and class. It’s worth remembering that this text was written at a time when the British ruled over roughly 200 million people across the world.

On the advice of his aunt, Copperfield in his early adult life decides to travel and discover what he wants to do for work, the equivalent of the modern day confused graduate’s gap year to south east asia. Copperfield invites his friend Steerforth to join him on his trip to Dartmouth to visit his dear childhood friends. Excited by this Steerforth exclaims “Let us see the natives in their aborginial condition!” The use of the words ‘native’ and ‘aboriginal’ to describe countryside englishmen suggests that they had a meaning related to class and perhaps regional distinctions in an english context which were then applied in colonial contexts from Australia to India to Nigeria. Mr Spenlows’ regard for solicitors as an “inferior Race of men” implies further that the concept of race as a category had meaning beyond colour, language and ethnicity. Somewhat different to how we conceive of ‘Race’ in contrast to ‘Class’ today.

References to the transportation of the poor and indebted to the colonies crop up throughout Copperfield, giving credence to the old addage that, ‘the English working class live in India.’ Yet Dickens constantly challenges the injustices of the victorian world and the lives the poor lead within it. The old logic justifying endless toil in the biblically derived proverb ‘idle hands are the devils workshop’ is beautifully challenged by Mr Wickfield when he states that, “Satan finds some mischief still for busy hands to do. The busy people achieve their full share of mischief in the world, you may rely upon it.” Another subversive and progressive notion comes in Dickens’ commentary on prisons when Copperfield visits a prison with traddles and observes the following…

“It was an immense and solid building, erected at a vast expense. I could not help thinking, as we approached the gate, what an uproar would have been made in the country, if any deluded man had proposed to spend one half the money it had cost, on the erection of an industrial school for the young, or a house of refuge for the deserving old.”

Newgate Prison, London 1850 “Punishment Cell”

It’d be remiss of me not to mention in reference to Class and Empire how Mrs Micawber laments on behalf of Mr Micawber. She describes how his country of birth has broken the social contract which should renumerate his hard work with employment,

“Here is Mr. Micawber, with a variety of qualifications, with great talent… And here is Mr. Micawber without any suitable position or employment. Where does that responsibility rest? Clearly on society.”

The imperial context again coincides with matters of class and poverty as the Micawbers find their only salvation to be in work found in Australia where they are justly rewarded for their hard work and talents.

Gender and Misogyny

Predictably we find in Copperfield attitudes and beliefs that today most of us find regressive and unjust. Misogynistic tropes come through most consistently but are not the only ones to be found in this otherwise beautiful novel. Age old European anti-semetism also rears its ugly head when the financial mechanism of ‘Bills’ in the mercantile world are attributed by Mr Micawber to, “the Jews who appear to me to have had a devilish deal too much to do with them ever since.”

Misogyny however rears its head more than once and seems to run through the book as a constant thread. We’ve already seen Mrs Micawbers intelligence and astuteness on display in her critique of a society which has failed Mr Micawber. Yet when Mrs Micawber shares her thoughts she cannot help but degrade herself (or Dickens cannot help but import female self-criticism onto his characters perhaps) and the value of her opinions in the presence of men. “I am aware that I am merely a female,” she says, “and that a masculine judgement is usually considered more competent to the discussion of such questions.” This kind of dismissal of female voices and a reinforcement of a subordinate gender identity is also clear when Copperfields mother lambasts herself saying, “for I very well know that I am a weak, light, girlish creature, and that he is a firm grave serious man.” It’s hard not to feel outrage when this kind of self-dehumanisation is so brazen in a story which otherwise portrays these characters in such sympathetic and heartfelt ways. Perhaps these attitudes cannot be disentagled from the victorian world in which they were written and yet I think to remain critical of the male voice of Dickens and the ways in which this may have shaped the female characters is wise.

Loneliness, heartache, depression

Dickens’ ability to capture emotion, particularly his portrayal of suffering is remarkable. I think my favourite scene of the whole book might be in the chapter ‘Martha’ where we see this literary flair at its best. As Mr Pegotty and Coppefield follow Martha on their quest for clues to find Emily through the “melancholy waste of road near the great blank prison” towards the river Dickens builds a sense of foreshadowing mirroring Martha’s despair with that of the “…pits dug for the dead in the time of the Great Plague… (where a) blighting influence (seems) to have proceeded from it over the whole place.” We come to a suicidal Martha pulled back from the edge of the haunting river, the only thing in all the world that she believes she is fit for. The physicality of her anguish is expressed so vividly, “sinking on the stones, she took some in each hand, and clenched them up, as if she would have ground them.” Oh the river.

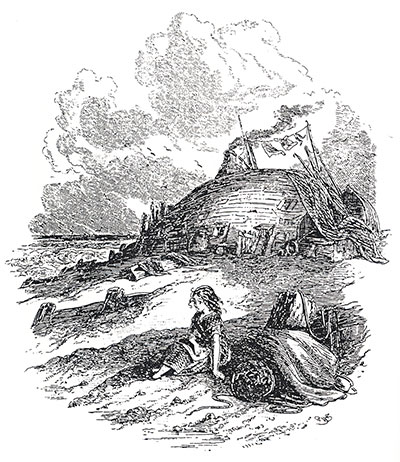

Halbot Browne (Phiz), Little Emily, 1849-50. Image from David Perdue’s Charles Dickens Page.

This tragic episode of near-suicide is not where I would like to end, nor with the aching of Copperfield’s “undisciplined heart” and the “wound with which it had to strive” following Dora’s death, but with this quote that sums up the melancholic beauty of Copperfields gentle soul as he journeys through his peculiar life, “though I still found them dreary of an evening, and the evenings long, I could settle down into a state of equable low spirits, and resign myself to coffee.”

Further Reading

- Demon Copperhead (2023) – Barbara Kingsolver

- Charles Dickens: A Life (2011) – Claire Tomalin

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) – Charles Dickens

- Bleak House (1852) – Charles Dickens

Leave a comment