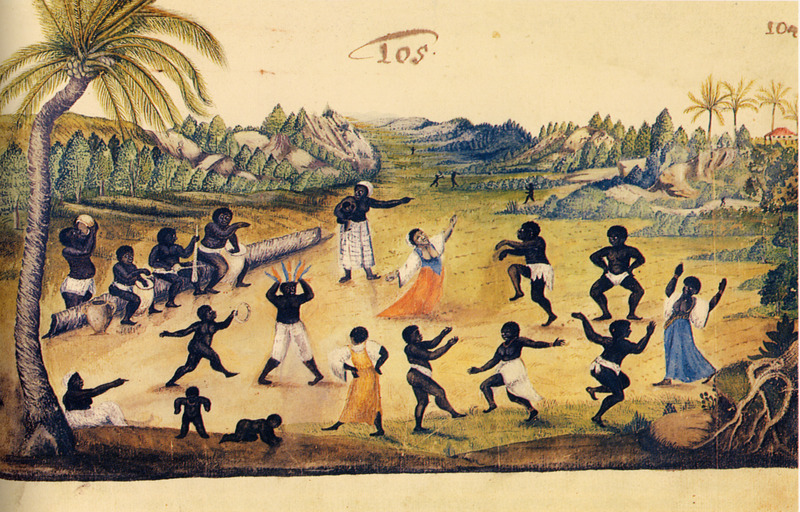

Divination Ceremony and Dance, Brazil, observed by Zacharias Wagener, a German mercenary for the Dutch West India Company, 1634.

As I journey through West African and Atlantic world history in the early modern period, I continue to ask myself: what misunderstandings distort our rendering of the historical experiences of enslaved Africans?1 How can we historians rectify and attune our understandings? Arthur Marwick poignantly argued that ‘often new labels are needed before new truths can be perceived.’2 This is true of Gender as a category of historical analysis in the context of the Middle Passage and the wider Atlantic World.3 The malleable nature of gender as a concept facilitates drawing connections across the vast space of the Atlantic whilst maintaining the integrity of historical specificities; particularly in the realm of cultural differences in ontology and ethnography.4 A sophisticated historical analysis attendant to ethnographic differences and cultural distinctions between peoples, and evolutions within peoples across space and time, is essential in understanding African Atlantic historical experiences in the early modern and modern world. I will begin by defining the terms ‘Long Middle Passage’, ‘Atlantic world’ and ‘Gender’ before demonstrating in turn how gender as a category of analysis provides insights across the three major sections of the long middle passage.

The ‘middle passage’ began as a maritime phrase among sailors working the triangular trade, referring to the stretch of the slave-trading journey from the West African coast to the American colonies connecting to the ‘homeward’ and ‘outward’ passages.5 The term is sometimes referred to as the ‘bitter passage’ and has served as a metaphor in Paul Gilroy’s laudable, though sometimes ahistorical, configuration.6 However, for the purposes of reading history from below and understanding the middle passage not simply as the leg of a trading circuit but in a deeper sense as a means of conceptualising the migrant journeys of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic world, the term ‘long middle passage’ serves us better.7 Marcus Rediker expands on this concept identifying two key stages for enslaved people; one from the societies of the West and Central African interiors to the coast and secondly across the Atlantic ocean to the Americas.8 I will address in this essay how attention to this longer journey has important implications for our understanding of the histories of enslaved people.

The ‘Atlantic World’ in its infancy was a European invention and should not be assumed to be a natural or stable phenomenon. However, therein lies its conceptual utility much like gender.9 William O’Reilly has identified how Atlantic studies were rooted in post second world war common interests among north Atlantic countries and have grown as a response to globalization; noting Godechot and Palmer’s presentation ‘The Problem of the Atlantic’ to the International Committee of Historical Sciences in Rome in 1955 as a watershed publication.10 David Armitage’s intervention reminds scholars to define and specify which ‘Atlantic’ they are referring to in their individual works. The Atlantic allows us to be transnational, international and national in our scope, but this should not undermine historical specificity.11 The geographic reorientation that an Atlantic approach requires, forces historians to research in an interdisciplinary manner; utilising linguistics, archaeology, oral history and many other methods.12 Moving beyond a solely literary approach is particularly important for the histories of Africans in the Atlantic world.13 Julius Scott’s ‘Common Wind’ thesis (1986) demonstrated how addressing trans and inter-colonial networks of communication and migration has major implications for understanding revolutionary thought. Scott contributed to historicising slave plantation life and the nuanced experiences of free people of colour, migrants and runaways in “Capitals of Afro-America”.14 Paul Gilroy envisioned a ‘Black Atlantic’ as a single yet complex unit of analysis, with the slave ship as a microcosm of cultural transformation and production.15 These transnational cultural exchanges in the Atlantic world, resulting from the intermixture of peoples hitherto unconnected, have since been conceptualised in the ‘motley crews’ of Linebaugh and Rediker.16 The Atlantic then, has geographic, economic and cultural dimensions that emphasise a reassessment of boundaries previously taken as historical constants.

Arguably the most significant historiographical contribution to the gender approach has been Joan Scott’s Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis (1986). Scott advocated a historicised approach to Gender that challenges the anachronism inherent in assuming fixed definitions of gender identities.17 Scott identified two major definitions of gender; firstly as a means of signifying relationships of power and secondly as a social construct based on perceived difference between the sexes.18 Ula Taylor has demonstrated how an awareness of gendered discourses can be used by historians in recovering the voices of women in archives.19 The development of the ‘History from below’ approach, as pioneered by E. P. Thompson, beyond a masculine and national framework has been a major historiographical achievement. However, the ‘Her-story’ approach as identified by Scott should not be regarded as synonymous with gender as an approach.20 Gender history is not intrinsically the history of women but the history of gendered historical experiences and ideas for all peoples. Gender enriches our understanding of a wide range of historical concerns in the context of the long middle passage and the Atlantic world.

The starting points of our long middle passage lie in the interior of West and West-Central Africa where enslavement took a variety of forms. Most enslaved Africans were captured because of warfare and kidnapping; the former a by-product of large-scale politically motivated factors and the latter small-scale criminal activity with enslavement as the primary motivation.21 Slavery also functioned as a judicial sanction for crimes of theft, sorcery, adultery, and murder. Those deemed as threats to the socio-political dominance of ruling elites were often banished and sold as slaves, seen in the case of the spiritual healer Domingos Alvares.22 Enslavement in some cases could be seen as a reaction to female social resistance, as Carolyn A. Brown posits in the cases of ‘troublesome’ women enslaved because they had broken social taboos.23

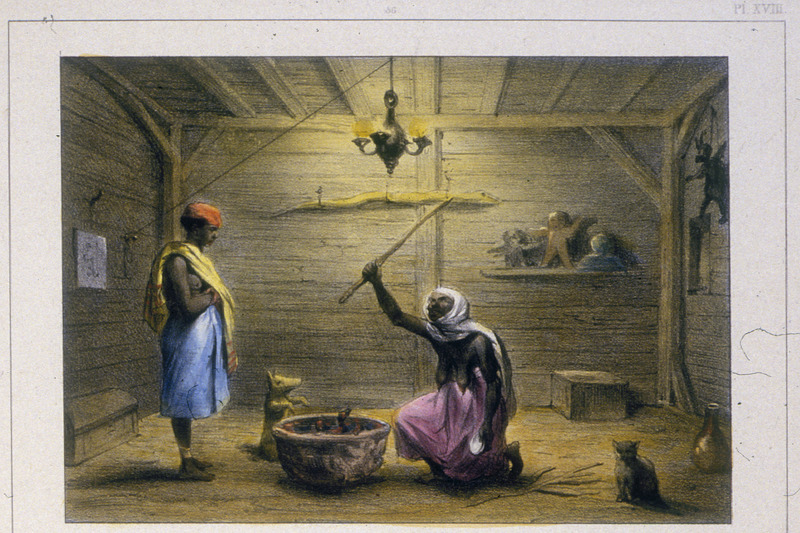

“The Mama-Snekie, or Water-Mama, Doing His Conjurations”, a female diviner using her spiritual powers to cure a child who is not present. Illustrated by Pierre Jacques Benoit (1782-1854) in Suriname, 1831.

Within the context of our long middle passage, we can identify short middle passages also. The uprooting of enslaved Africans could precipitate a migration of a hundred kilometres or less from their homes to that of their enslavers.24 These smaller journeys should also be considered alongside the seismic forced migrations of 11.7 million slaves across the Atlantic between 1500 and 1800 and 2.3 million across the Sahara, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean to the Muslim world between 1600 and 1800.25 Manuel Barcia has identified how the gendered demography of groups of slaves travelling to the Atlantic coast varied significantly depending on region. Groups migrating from Oyo, Sokoto, Borgu, Nupe and Borno consisted predominantly of males whereas the male-female ratios were more balanced in the case of Dahomey and the southern Yoruba states. In short, men were likely to journey with fewer women the farther from the Atlantic coast they came.26 These differing middle passages also impacted the gendered roles enslaved Africans performed. Enslaved women for instance were likely to engage in domestic service and work in harems if sold into the trans-Saharan trade, as labourers and mothers in the trans-Atlantic trade (less likely than the trans-Saharan, given the overwhelming preference for men in the Atlantic trade) and as soldiers, labourers, or wives within Africa.27 The implications for the lived experiences of enslaved women especially were profound given their capability to offer reproductive and productive labours unlike men. For instance, life as a soldier slave would differ substantially from that of a labourer giving birth to children and suffering sexual exploitation and violence on an American plantation. Female soldiers could be found in African armies across West Africa. Analysis of the Dahomean amazons or “minos”, literally meaning “our mothers”, forces one to challenge European gendered assumptions that associate femininity and motherhood with passivity. These women, some “women of distinction and noble birth” who led men into battle, call into question our misunderstandings and refine our constructions of African histories. These histories can contain profound Atlantic dimensions. Manuel Barcia’s study demonstrates how African military techniques and strategies were fundamental in slave resistance, understood by enslaved African soldiers as acts of warfare, in Bahia and Cuba and had an equally high representation of female soldiers, demonstrating how African gender roles travelled across the middle passage.28 The gendered experiences for enslaved Africans working for Europeans on the Atlantic coast differed substantially from those in the interior.

Dahomey Amazons with the king at their head, going to war, observed by Archibald Dalzel in Benin, 1793.

Historians should recognise that the Atlantic slave trade was a series of differing slave trades, particularly given the significant demographic differences. G. Ugo Nwokeji’s analysis of gender concerns in the Bight of Biafra highlights a greater degree of demographic variation along the West and Central African coastline than has been appreciated by scholars.29 Whilst gender as a category of understanding in an African context should be used cautiously with an awareness of potential violations of African ethnographic selfhood, we must be attendant to the gendered divisions of labour among those found in West African societies.30 Nwokeji identifies how female slaves in the local economy generally engaged with weeding and planting vegetables whereas males tilled the ground, planted yams, climbed trees and built.31 We know that a significantly larger percentage of women entered the Atlantic trade from the Bight of Biafra than any other region.32 Whilst this is a notable variation, Nwokeji warns against assuming economic causes and directs us to questions of African conceptions of gender in determining the lived experiences of enslaved and free Africans. Why would the Igbo and Ibibio kill twins when selling two or more children gained a higher price? And why did the Aro regions warriors decapitate men in war regardless of the financial benefit of selling them?33 These questions raised by Nwokeji echo John Thorntons contention that Africans engaged decidedly in processes of enslavement and sale according to African socio-political imperatives.34 A gender approach can also provide insights into economic history. Lovejoy and Richardson demonstrate how a focus on price differentials by gender has substantial implications for historical understanding of slave markets.35 This example confirms the utility of gender as a paradigm that encourages one to assess evidence and ask historical questions in new ways that implicate disciplines beyond the realm of social or women’s history where gender concerns have often been relegated to.36

Aboard the slave ship enslaved Africans entered a peculiar multi-ethnic and multicultural microcosm consisting of Europeans of many nations, slave and free, sailors and captains, men, women, and children.37 When assessing the historical experiences on the ‘floating dungeon’ as it left the ‘door of no return’ our understanding is enriched by asking how meanings of gender were constructed through the actions and relationships of these ‘motley’ actors.38 Alexander Byrd has raised the question of ethnic formations both during the paths to the coast from the interior of Africa where enslaved people had already experienced dislocation and migration prior to their oceanic journeys, and aboard the slave ship. African ‘national’ or ‘ethnic’ identities such as Igbo, can be taken for granted if historical categories are not researched and interrogated sufficiently. Byrd demonstrates that ‘Igbo’ was an invented ethnicity, forged as an amalgamation of the Aro, Ngwa, Aboh peoples of the Biafran interior within the context of the experiences of enslavement during the early stages of the long middle passage.39 This cultural homogenisation was facilitated by commonalities in language, cosmology, philosophy, and politics, but demonstrates the evolutions of culture resulting from historical forces. Could gender ideas have undergone change in a similar manner? European gendered attitudes are prevalent in the sources more so than African voices; a constant impediment when using the colonial archive. Yet reading against the grain with a history from below approach and attention to African experiences and perceptions one can refine our (mis)understandings of African life on the slave ship. Strictly regulated segregation aboard slave ships was common, with men in the hold below, women and children generally unchained between decks allowing for greater corporeal freedoms and better health conditions when compared with those enslaved men experienced with lack of air flow, surrounded by excrement with, “not so much room as a man in his coffin,” as one guinea surgeon observed.40 Barricades were erected to separate men and women when above deck, a conscious attempt by the captain to disrupt social relations. However, enslaved Africans continually breached these barriers in efforts to be with each other as lamented by slave captains and sailors.41 Were these instances acts of defiance of European gendered structures of separation? Another Guineamen believed that women kept higher spirits than men, “this Despondency, with the Men, continues in general – It wears out sooner with the Women.”42 Perhaps there is truth in this given the comparable conditions discussed above, however the very generalisation that posits a chasm between female and male experiences reveals European assumptions concerning the gendered male/female binary. Was this binary true for Africans across thousands of slave ships as they understood shipboard life? I doubt it. When sailors distributed beads and baubles to enslaved women and girls exclusively, we see gender roles imposed. Further, gendered assumptions could be read in terms like “fanciful” used to describe the “ornaments for their persons” that enslaved women fashioned.43 Aboard the Hudibras Captain Evans named a favourite female slave ‘Sarah’; regarded as a graceful and beautiful dancer by the ship’s sailors. Marcus Rediker asks whether the choosing of a biblical name reveals the captains hope that much like Abraham’s wife she would remain, “submissive and obedient… during a long journey to Canaan.”44 Enslaved Africans had to address the gendered tenets aboard the ship, either adopting, rejecting, or transforming European ideas from a particular African cultural perspective. These cultural forces continued to be prevalent as enslaved Africans journeyed to American plantations.

Shows the two major slave decks and how enslaved Africans were crammed into them. The top shows the deck which held females. The bottom shows the plan of the main deck where males were kept. Diagram of the Decks of a Slave Ship, 1814.

As we arrive at the latter stage of our long middle passage it’s worth noting that this was not necessarily the final passage Africans would travel. Gregory E. O’Malley, mirroring Scotts’ emphasis on intercommunication and movement in the Americas, highlights how intercolonial trades of enslaved Africans within and between the Caribbean and North America have been neglected and should be researched further if the variety of African life in the Atlantic world is to be appreciated.45 The journeys of notable Africans like Domingos Alvares and Olaudah Equiano who travelled extensively across the Atlantic world and gained their freedoms were of course exceptional.46 Most enslaved people in the Americas suffered and faced limited movement, horrific tortures, cultural violence and premature deaths on plantations.47 However, their stories are fundamental in challenging assumptions of static ‘existential conditions’ of enslaved people and further can indicate the possible beliefs and thoughts of other Africans whose voices are absent from the Atlantic archive.48 My primary concern is the experiences of enslaved Africans, but it should be noted that European gendered ideas were subject to change just as African ideas were in the Atlantic world. Mary Norton refers to the gendering of the ‘feminine private’ in the early eighteenth century, and Amussen and Poska contend that Atlantic interactions have had an impact on European societies and culture. They encourage historians to challenge the cultural cohesion of the nation state rooted in the nominal distinction between metropole and periphery. This separation is an arbitrary division that occludes understanding the Atlantic world fully.49 James Sweet highlights scholarly neglect in the study of same sex relationships in slave communities and highlights how unbalanced sex ratios and African flexibility in gender categories contribute to these relationships.50 Sweet’s case study of Antonio is particularly enlightening, an enslaved African working in 16th century Lisbon who restyled their clothing, exhibited ‘female’ behaviours and sold sexual favours to many European men under the name ‘Vitoria’ near the docks.51 Individuals like Antonio/Vitoria, represented a ‘third gender’ unfamiliar to the Portuguese, but accepted in Benin society.52 For instance, the quimbandas of central Africa and the Shango priests of Yoruba, were regarded as ‘sodomites’ and ‘transvestites’ by Europeans. Yet from an African perspective, these individuals exercised gendered behaviours as part of rituals that were motivated by specific spiritual beliefs.53 The gross misunderstandings many Europeans exhibited in their contemporary observations must not be reproduced by historians. A utilisation of the gender approach assists us in avoiding this pitiful and upholding historical and ethnographic integrity in the Atlantic world. John Thornton’s sophisticated excavation of cultural aesthetics in the Atlantic world is revealing. In some cases, African hair styles were influenced by Christian gender norms and carried across the Atlantic; the covering of women’s heads in coastal African societies being a prime example.54 The calenda, a dance originating in Allada in modern day Benin, journeyed to the Spanish who according to Jean-Baptiste Labat “…learned it from the Negroes, and it is danced in that way in all the Americas in the same way as by the Negroes.” Calenda was performed with certain gendered arrangements such as rows of men facing women. However, the European reaction is most interesting from a gender perspective. Labat, like the authorities of the French West Indies and other Europeans, tried to ban the dance due to supposedly ‘lascivious’ and ‘obscene’ hip movements.55 These actions did not conform with European, particularly Christian, gendered norms of female behaviour. The cultures of the Americas underwent substantial revolution and transformation in a process termed ‘creolisation’. Questions centred around the nature of gender ideas and gendered relations as part of this phenomenon should be asked by Atlantic historians. Africanists especially, have warned against assumptions concerning the speed and nature of cultural change in Atlantic societies.56

Within the many historical moments of the long middle passage and the Atlantic world one sees a plethora of ways in which gender enlightens historical understanding of the lived experiences of enslaved Africans. Relationships between and within cultural groups, beliefs, and actions of a range of European and African people, demographic and economic systems, the nature of enslavement for Africans and the nature of enslaving for Europeans and Africans, are all permeated by gender concerns. Gender of course stands beside many other insightful approaches; race and class most notably. However, gender has been understudied and underutilised compared with race and class in histories of the Atlantic world. Gender should be considered by all historians as one valuable method of refining our (mis)understandings of the histories of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic world.

Further Reading

- Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese world, 1441-1770 (2003) – James Sweet

- Gender and The Politics of History (1988) – Joan Wallach Scott

- The Slave Ship (2007) – Marcus Rediker

- Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (1997) – Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí

- A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250-1820 (2012) – John K. Thornton

Footnotes

- A note on terminology: I will be using the term ‘enslaved Africans’ rather than ‘slave’ to highlight the mutability of African lives in the Atlantic world and to refrain from indulging the dehumanising tendency of the ‘social death’ approach. See: Toby Green, A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution (London: Penguin Books, 2020), p. xxxiii., Frederick Cooper, Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History (Berkeley: California, 2005), p. 17., Vincent Brown, ‘Social Death and Political Life in the Study of Slavery’ The American Historical Review, 114 (2009), p. 1246. ↩︎

- Arthur Marwick, The Nature of History (London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd, 1970), p. 150. See also, Eric Hobsbawm, On History (London: Abacus, 1998), p. 17., John Arnold, History: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 67-68. ↩︎

- Joan Wallach Scott, Gender, and The Politics of History: 30th Anniversary Edition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), see Scott’s article, first published in 1986, ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis’, reprinted in chapter 2, pp. 28-50. ↩︎

- James H. Sweet, ‘Reimagining the African Atlantic Archive: Method, Concept, Epistemology, Ontology’ The Journal of African History, 55 (2014) 147-159. ↩︎

- Emma Christopher, Cassandra Pybus and Marcus Rediker in Many Middle Passages: Forced Migration and the Making of the Modern World ed. by Emma Christopher, Cassandra Pybus and Marcus Rediker (London: University of California Press, 2007), p. 1. ↩︎

- Rinaldo Walcott, ‘Middle Passage: In the Absence of Detail, Presenting and Representing a Historical Void’ Missing and Missed Subject Politics Memorialisation, 44 (2018), p. 60., Joan Dayan, ‘Paul Gilroy’s Slaves, Ships, and Routes: The Middle Passage as Metaphor’ Research in African Literatures, 27 (1996), p. 7. ↩︎

- On the ‘History from Below’ approach see: E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1963)., Hobsbawm, On History (London: Abacus, 1998), pp. 266-286., Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (London: Viking Press, 1972)., Peter Linebaugh & Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (London: Verso, 2000)., The Future of History from Below: An Online Symposium, ed. by Mark Hailwood and Brodie Waddell (2013) (URL: https://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/history-from-below/). ↩︎

- Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (London: John Murray Publishers, 2008), p. 75. ↩︎

- David Armitage, ‘Three Concepts of Atlantic History’ in The British Atlantic World, 1500-1800, ed. by David Armitage and Michael J. Braddick (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), p. 12. ↩︎

- William O’Reilly, ‘Genealogies of Atlantic History’ Atlantic Studies, 1 (2006), p. 66. ↩︎

- Armitage, ‘Three Concepts of Atlantic History’, pp. 26-7. ↩︎

- Alison Games, ‘Atlantic History and Interdisciplinary Approaches’ Early American Literature, 43 (2008), pp. 188-9. ↩︎

- Jan Vansina, Oral Tradition as History (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985)., John K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998). ↩︎

- Julius Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American currents in the age of the Haitian Revolution (New York: Verso, 2018), pp. xiii, 15, 44. ↩︎

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), pp. 15, 17. ↩︎

- Peter Linebaugh & Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (London: Verso, 2000), p. 213. ↩︎

- Joan Wallach Scott, Gender and The Politics of History: 30th Anniversary Edition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), pp. 40-41. ↩︎

- Scott, ‘Gender and The Politics of History’, p. 42. ↩︎

- Ula Taylor, ‘Women in the Documents: Thoughts on Uncovering the Personal, Political, and Professional’ Journal of Women’s History, 20 (2008), p. 195. ↩︎

- Scott, ‘Gender and The Politics of History’, p. 20. ↩︎

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 3-4. ↩︎

- Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery, p. 4., James H. Sweet, Domingos Álvares: African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, 2011), p. 22. ↩︎

- Carolyn A. Brown in Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies, ed. by Sylvianne Diouf (Oxford: James Currey, 2003), pp. 221-222. ↩︎

- Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery, p. 3. ↩︎

- Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery, pp. 61, 66. For the most comprehensive database on slave-trade statistics see, The Slave Voyages Database (URL: https://www.slavevoyages.org/about/about#history/1/en/). ↩︎

- Manuel Barcia, West African Warfare in Bahia and Cuba: Soldier Slaves in the Atlantic World, 1807-1844 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 41-42. ↩︎

- Paul E. Lovejoy and David Richardson, ‘Competing Markets for Male and Female Slaves: Prices in the Interior of West Africa, 1780-1850′ The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 28 (1995), p. 284. ↩︎

- Barcia, West African Warfare in Bahia and Cuba, pp. 38-39. ↩︎

- G. Ugo Nwokeji, ‘African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic’ The William and Mary Quarterly, 58 (2001), p. 48. ↩︎

- Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí, Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), p. 31. ↩︎

- Nwokeji, ‘African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic’, p. 56. ↩︎

- Nwokeji, ‘African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic’, p. 49. ↩︎

- Nwokeji, ‘African Conceptions of Gender and the Slave Traffic’, p. 50. ↩︎

- Thornton, Africa and Africans, p. 125. ↩︎

- Lovejoy and Richardson, ‘Competing Markets for Male and Female Slaves’, p. 285. ↩︎

- Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, p. 21. ↩︎

- Linebaugh & Rediker, The Many Headed Hydra, p. 213. ↩︎

- Rediker, The Slave Ship, p. 106. ↩︎

- Alexander X. Byrd, Captives & Voyagers: Black Migrants Across The Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008), pp. 31-32. ↩︎

- Byrd, Captives & Voyagers, pp. 35-6., Stephanie E. Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American diaspora (London: Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 143. ↩︎

- Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery, p. 76. ↩︎

- Byrd, Captives & Voyagers, p. 43. ↩︎

- Byrd, Captives & Voyagers, p. 34. ↩︎

- Rediker, The Slave Ship, p. 19. ↩︎

- Gregory E. O’Malley, ‘Beyond the Middle Passage: Slave Migration from the Caribbean to North America 1619-1807,’ The William and Mary Quarterly, 66 (2009), pp. 127-129., Scott, The Common Wind, p. 44. ↩︎

- Sweet, Domingos Álvares., Olaudah Equiano: The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings ed. by Vincent Caretta (London: Penguin Books, 2003). ↩︎

- Michael Craton, Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press), p. 15. ↩︎

- Cooper, Colonialism in Question, p. 17. ↩︎

- Mary Beth Norton, Separated by their Sex: Women in Public and Private in the Colonial Atlantic World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011), p. 90–91., Susan D. Amussen and Allyson M. Poska, ‘Shifting the Frame: Trans-imperial Approaches to Gender in the Atlantic World’ Early Modern Women, 9 (2014) 3-24. ↩︎

- James H. Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese world, 1441-1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), p. 50-51. ↩︎

- James H. Sweet, ‘Mutual Misunderstandings: Gesture, Gender and Healing in the African Portuguese World,’ Past and Present, 203 (2009), p. 128. ↩︎

- Sweet, Recreating Africa, p. 54. ↩︎

- Sweet, ‘Mutual Misunderstandings’, pp. 132-133. ↩︎

- John K. Thornton, A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250-1820 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 356. ↩︎

- Thornton, A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, pp. 395-396. ↩︎

- Find valuable theoretical and empirical critiques of creolisation in James H. Sweet, ‘Reimagining the African Atlantic Archive: Method, Concept, Epistemology, Ontology’ The Journal of African History, 55 (2014) 147-159., and Manuel Barcia, ‘A Not-so-Common Wind: Slave Revolts in the Age of Revolutions in Cuba and Brazil’ Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 31 (2008) 169-194. ↩︎